Most of the electric power industry followed Texas winter storm Uri and the associated rolling outages in February 2021. Millions of customers were without power for extended periods. Sub-freezing temperatures lasted for days. Water systems dependent upon electricity for pressure control also failed, leaving many without water as well. Over 100 Texans died as a direct result.

The storm happened when the Texas legislature was in session — a rather odd coincidence since the legislature only meets every other year and then for only a few months. Reaction from the legislature was swift: The Public Utility Commission of Texas (PUCT) was commissioned to examine the current rules under which the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) handles the power market in Texas and improve these rules to ensure this type of catastrophe does not repeat.

Among the dozens of concerns that have come out since the disaster is the idea that Texas may be too dependent on intermittent power sources, namely, wind and solar power. Due to freezing issues, some wind power facilities did not generate during the storm. Solar was likewise curtailed due to the heavy snow that fell across the state. Had more reliable, dispatchable power been available, the reasoning goes, the state could have overcome the issues with the intermittent sources.

The actual root causes of the power emergency went far beyond renewable energy underperformance; there were shortages of natural gas for power generation, some power plants tripped offline in the low temperatures, and so on. But the dispatchable generation of power was clearly seen as an issue.

Dispatchable energy meaning

Dispatchable energy can be programmed quickly on-demand by power grid operators. As a result, dispatchable energy is ready for use when the market is in need. In contrast, non-dispatchable energy refers to renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind, which can’t be sourced when needed.

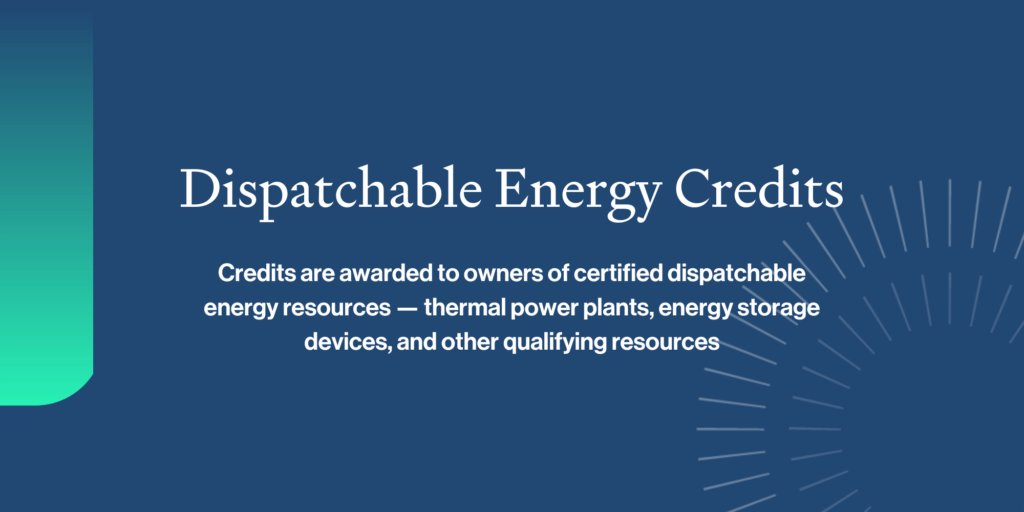

Dispatchable Energy Credits

PUCT proposed a recommendation to set up a system for incentivizing the investment in power infrastructure that’s truly dispatchable. The concept is that Load Serving Entities (LSEs) must show that a certain percentage of their load obligation is covered by firm, dispatchable power (instead of intermittent power). This process would essentially create a Dispatchable Portfolio Standard for LSEs.

These LSEs could satisfy the standard by purchasing or generating Dispatchable Energy Credits (DECs). These credits are awarded to owners of certified dispatchable energy resources — thermal power plants, energy storage devices, and other qualifying resources. If an LSE owns such resources, they can self-satisfy the portfolio requirement, but if they don’t have enough, they could purchase these from other market participants who have excess.

The intent behind creating the DECs is to incentivize the investment of power-generating resources that are dispatchable when needed and not dependent on natural forces like the sun and wind to produce power. Presumably, if there’s an overall shortage of DECs in the market, their price will rise, leading investors to view DECs as an additional revenue stream for a potential project.

This approach is identical to one taken in the early 2000s with the adoption of the Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard in Texas. Load-serving entities had to satisfy a specific portion of their power requirements with renewable energy. Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) were awarded to wind and solar farms; these were purchased by the LSEs to satisfy the portfolio standard, and the highly successful renewable energy portfolio in Texas got off the ground. The extra revenue stream provided by the RECs enabled many projects to be accomplished that would not have otherwise succeeded.

Are there issues with DECs?

The first issue to address is: What resources would qualify to be awarded DECs? Initially, the guidance applies only to new generation resources. Further, the suggestion is that the resources must be able to ramp up to full load in five minutes or less and have a heat rate of 8,000 British thermal units/ kilowatt-hours or less. For batteries, there is a two-hour duration minimum to qualify.

These requirements sound reasonable, but if it only applies to new generation, then the vast majority of ERCOT’s current dispatchable fleet would not qualify. Further, with the DEC program only addressing new generation, what portfolio standard would then apply to LSEs? Would the PUCT set a goal of 3,000 megawatts of new generation and distribute the goal among the LSEs based on load ratio share? What about LSEs that have their obligation completely covered by existing dispatchable resources — will they be forced to purchase DECs nevertheless?

The five-minute requirement has also been questioned — how much more effective is this than the current 10-minute requirement for qualifying for Responsive Reserve Service (RRS)? Many quick-start combustion turbines can meet the 10-minute requirement but will not reach the five-minute goal. Similarly, the 8,000 Btu/kWh heat rate target isn’t achievable for most quick-start combustion turbines, which operate around 9,000-9,400 Btu/kWh. These two criteria eliminate some of the most flexible resources in the market and the ones most easily sited, permitted, and quickly constructed.

A more significant issue revolves around how much of an incentive the DECs will actually be. It’s proposed that the DEC procurements be limited to 12 months in advance. Some market participants believe this doesn’t offer enough revenue certainty required by lenders and other capital investors. A given project’s economics revert to basic calculations related to the forward price curve, probability of scarcity pricing, and other issues currently unfavorable to new investment.

Where from here?

The PUCT is currently working with consultants to develop a partial redesign for the ERCOT market in at least a few areas. The targeted aspects are reforms to the Operational Reserve Demand Curve (ORDC) price formation mechanism to increase prices when the market approaches scarcity conditions. Adjustments to how LSEs ensure their load obligation is covered by firm generation; enhancing the role of Demand Response (DR) in the market and reforming the method for deploying Emergency Reserve Service (ERS); and several other areas. Implementing some type of Dispatchable Energy Credit program is among the future changes being analyzed.

The proposed reforms to the market will undoubtedly stir much debate and analysis in the coming months and years. Some actions will be easy and quick to implement, while others will take more time. The eventual state of the market may not even contain Dispatchable Energy Credits. But faced with a rapidly growing market, the Texas grid must evolve and adapt to ensure no repeat of the sweeping power outages that crippled the state in 2021.

Interested in more content about ERCOT? Read John Bonnin’s blog post, “Energy Storage Integration In the Texas Power Market.”