“I studied electrical power generation for two reasons,” PCI co-founder Art Breipohl says in his autobiography. “There was more money in both the capital cost and the fuel cost of generation, and there was very little study of generation in electrical engineering programs, implying there could be a better chance of finding a new method of saving electrical utilities money.”

It’s always enjoyable to hear cogent thinking, and it’s doubly satisfying to be able to look back and reflect on how that thinking has been borne out.

Art’s biography is fascinating to anybody interested in how and why PCI was formed, as well as for those looking for clues to its success and the core capabilities that will be the foundation for its future. In this frank and often funny account of Art’s life, we’re invited to observe how he thinks about the world — logically, rationally, and originally — and, through Art, understand PCI more deeply. It’s easy to trace many of PCI’s cultural traits back to his uniquely pragmatic perspective.

Living PCI’s values

Power Costs, Inc. (PCI) was formed on June 9, 1992. At the time, Art Breipohl and Fred Lee were professors in the Electrical Power Program at OU, a program Art established. For a few years, the pair had been laying the groundwork for PCI, a company that would grow into a successful international software company whose products are used by 70% of U.S. Fortune 500 Utilities.

Art’s autobiography traces the founding of PCI back to his early years. It’s a book about a man finding his path, always on the lookout for meaningful problems to solve, and continuously improving to be ready to face the next challenge.

A talent for mathematics led Art into engineering. “I really did not know what an engineer did,” he says, “but I was told that math and physics were the basis of engineering.” In 1955 he began active service with the U.S. Army and opted to increase his draft from two to three years to work on nuclear weapons. He was assigned to the 832nd Ordnance Battalion and later went to work at Sandia Corporation, where he was tasked with determining the probability of nuclear weapons accidentally exploding.

At the time, of course, he had no conception of how engineering and the mathematics of probability would inform PCI’s early products, but it’s interesting to watch that road unfold in front of him through the story of his life.

Art was always careful to play to his strengths and cover his weaknesses. He turned down a promotion to a supervisor’s job at the reliability department at Convair because “I did not think my talents and shortcomings were best suited for management.”

Seen through the lens of PCI’s values, these are instances of Art demonstrating the PCI value he coined as “enlightened awareness.” Art thinks like an engineer, rationally, always seeking clarity on what is happening, especially about the one thing it’s most difficult for us to be objective about — ourselves and our limitations. At PCI, we’re all called to do the same.

As PCI co-founder Fred Lee noted in a recent company-wide email, “My dear friend Dr. Art Breipohl once told me – we all have self-interest, but we should only practice “enlightened” self-interest. His wisdom has had a very profound impact on me.”

Profiting From Your Mistakes

Later in his career, Art applied for the dean’s position at Kansas University (KU) and narrowly missed out on it. He relates it as a crushing blow, but one he ultimately believes he profited from because it “opened up another path that was much more rewarding.” The path to co-founding PCI.

Following this big disappointment, Art went on a sabbatical at Stanford University to lick his wounds and decide what he wanted to do with the rest of his career.

“I did not have the knowledge nor the inclination to manufacture a product,” Art says, “and while I could find work as a consultant, it was much better to have a product that one could essentially sell many times rather than selling one’s effort one at a time as a consultant. There was a group in the engineering economics systems department that was working as consultants in the power industry. I decided that perhaps I could develop a method for electrical utilities to decrease their costs and sell this to a large number of utilities. This became my big-picture goal.”

It’s an excellent example of the kind of clear thinking characteristic of Art throughout his autobiography, and this and other recollections are recorded with remarkable clarity for a man in his 90s (if Art doesn’t have a closet of journals he referenced to write this autobiography I’ll eat my hat!).

Connectedness

At this point, PCI co-founder, Fred Lee, enters Art’s story.

“I was indeed fortunate to have a graduate student by the name of Fred Lee, who was an employee of Black & Veatch, a major power consulting firm in Kansas City,” Art says. “He was very bright and more experienced than I in electrical power, and I started him on a dissertation that involved unit commitment, a study of when each of the many electrical generating units owned by an electrical company should be turned on and off. This was quite a difficult problem, and no general solution was known.”

The strands began to come together for Art when he accepted the OG&E Professor in Electrical Power position at the University of Oklahoma (OU) in 1984. It was here that Art and Fred laid the groundwork for their future company.

The theme of Connectedness (another PCI value) runs strongly through this period of Art’s life. Having overcome his earlier social awkwardness, Art has matured to the point where he can harness the power of those around him to make big things happen.

“I visited Tom Hoke, the vice president of engineering at OG&E,” Art says, “and proposed that I would be an unpaid consultant and visit OG&E once a week. I began to establish an advisory board for the electrical power program. I also began recruiting an assistant professor for the program. All of these steps were designed to establish a quality power program at OU and also to do things that might aid in developing a company that sold a product to electrical utilities.”

“With quite a lot of help from (my wife) Shirley, I persuaded Fred Lee and his wife, BinRo, to leave Black & Veatch and for him to join OU as an assistant professor.”

Forming a Company

Art spoke to Tim Harlow, CEO of OG&E, about his goal to form a company that would “sell a computer program that would schedule electrical generation.”

Tim was enthusiastic. “I think he wanted this to be a model for professors starting companies,” Art says, “and he thought that this would be good for Oklahoma and OG&E.”

Art secured three years of support from OG&E for the Power Program at OU, while Fred and his students made good progress on the development of a program that would schedule power generation.

In 1988 Fred published a paper on scheduling generation. Harris Control, an Energy Management System (EMS) for generation control, reviewed it and hired Fred as a consultant while they coded a version of his method of generation scheduling into their software.

Harris had an opportunity to obtain a large contract from Allegheny Power, but Allegheny wanted Harris to include some fuel and emission constraints and a method for long-range generation planning consistent with the method used for short-term generation scheduling. Harris agreed to hire Fred and Art as consultants if they could persuade Allegheny that they could add these features. They both flew to Florida and gave a technical seminar to Allegheny Power and Harris (the first of many). It was successful, and they negotiated a contract.

As a result, on June 9, 1992, Power Costs, Inc. (PCI) was formed.

“We formed a company!” Art writes with obvious pride.

Harris got exclusive rights to the scheduling generation program for two years. But PCI maintained the rights to market this program in a standalone market (i.e., not as part of an energy management system) after two years, a clause that left the path clear for Art and Fred to sell the software independently in the future.

Acquiring Customers

One of the major hurdles to starting a company is finding customers and convincing them to buy your product. Early on, Art and Fred hit upon a method that played to their academic credentials and their combined experience teaching.

“In 1994, Fred and I taught a short course in Las Colinas (Texas) under the sponsorship of the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI),” Art writes. “This course went very well, and, significantly, the companies that sent representatives were the same ones to which we sold our first standalone product. The fact that we could sell through teaching a short course was a valuable lesson for us.”

It’s a lesson that PCI continues to reap the benefits of to this day.

Harnessing Disruption in Power Markets

Initially, PCI’s product was not a great fit for the market. “We were told by our friends in the power business that while they believed that our program could save them a few percent in fuel costs, this was simply a pass-through cost (an expense that could be passed through to their customers), and it did not make any difference in their profit.” The formation of PCI in 1992 was fortuitously timed. The Energy Policy Act of the same year attempted to enhance competition in the electric power industry by lifting legal barriers, and FERC Orders 888 and 889 followed in 1996, promoting generation competition. “With this new order, electricity was traded, and lower costs meant more sales and more profits,” Art writes.

The fledgling PCI’s first standalone contract came right around Art’s 63rd birthday. PCI had received an RFP from Northern States Power for generation-scheduling software, and the chairman of the selection committee was one of the students on the course that Art and Fred had taught in Las Colinas. Securing that first contract was “a great morale booster.”

More customers followed on the heels of the Northern States. In 1996 PCI secured Entergy as a customer, then CSW, and then Texas Utilities. “These companies were represented in our short course and also had representatives on our advisory board for the OU power program,” Art writes, highlighting the crucial importance of connectedness to the early success of PCI. “Other contracts that we received were due to references from these companies or to the new salesperson whom we hired — Walter Hobbs.”

On Hiring

As PCI grew, Art entered yet another phase of life: helping scale a company. His attention turned to finding, recruiting, and training talent. “I sought employees who were smarter than I was,” he says, “and certainly better at doing the things that I had done for the company when I had been doing those jobs … In particular, we hired Sandy Ho to replace me as the chief financial officer, and I trained her in some of the actions that were unique to PCI and particularly negotiating contracts.”

In 2000 PCI’s income was $3.25 million. At this point, Art turned 69 and began to plan his retirement from OU and PCI.

A Long and Productive Retirement

Art and Shirley built a house in Norman at retirement and went on several cruises to exotic destinations all over the world. Art became involved in local politics, specifically in support of building a new senior center in Norman.

“When we were preparing to leave Norman,” Art says, “the senior association held a going-away party for me at Bob Thompson’s [Midway] deli. It was well attended, and the mayor presented me with a key to the city. (I have not been able to find the lock).”

Today, Art and Shirley live in the Splendido retirement community in Tuscon, Arizona, where he still teaches, including classes in statistics and electricity to other residents, all of whom are over 80. “You have to consider your audience,” he told me over the phone, with his usual wit. “It used to take me an hour to prepare a one-hour lecture, and now it takes me a week!”

Art began his autobiography in 2019 when he moved into Splendido and completed it in 2021. “It kept me off the streets,” he reported.

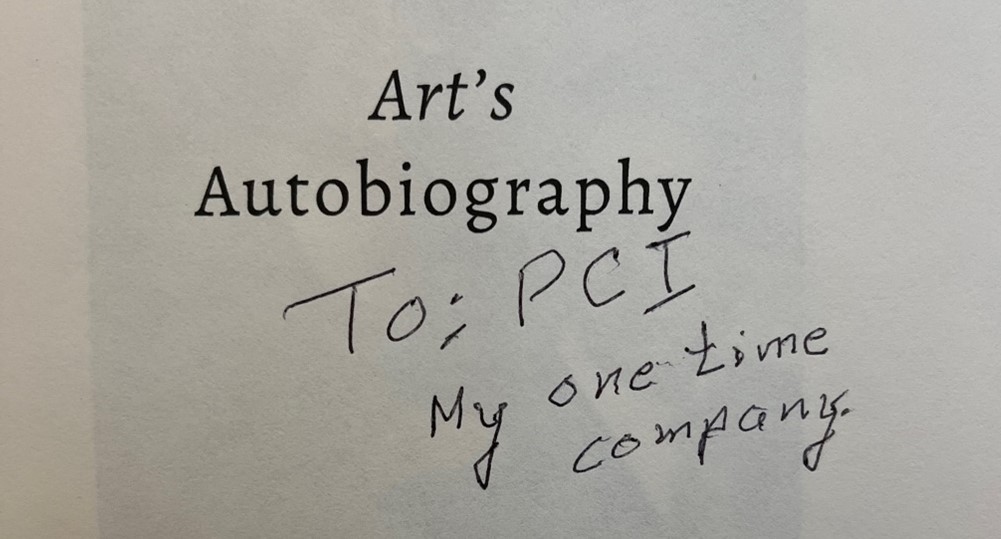

If you’re interested in borrowing PCI’s copy (and I highly recommend it), please reach out to let me know.

Summary: Ethics Within the World of Work

Art helpfully summarizes his autobiography, and the significant learnings of his life, with all the economy of an engineer.

“I think that the characteristics and attitudes that led to my success in work were that I established goals for myself and concentrated on achieving them, I tried to associate with people who were smarter or more capable than me, and I tried to profit from my setbacks.”

Art wrote this final section of his autobiography for his grandchildren, but we at PCI are also his beneficiaries, so it’s easy to imagine he’s addressing us too when he signs off by saying, “Please consider ethics, select smart and ethical associates, use setbacks as learning experiences, and set goals for yourself. You can do it!” — Arthur McHarg Breipohl.

If you’re interested in learning more about the founding of PCI, check out “30 Years of Growth and Learning” on our blog.